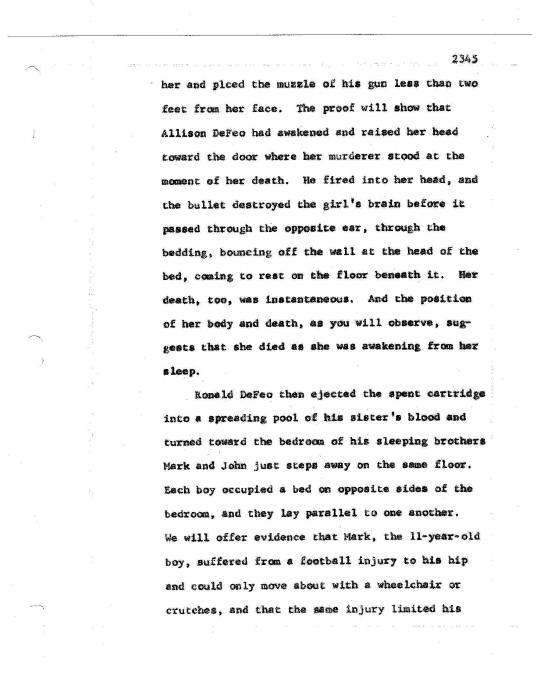

On January 15, 1975, Butch’s then-lawyer, Jacob Siegfried, motioned the court to be permitted “the right to examine, inspect, copy, photograph, or make and take photostatic copies of the original notes of the arresting officers, together with police reports containing statements of the witnesses…”

Siegfried insisted these items were crucial in his affidavit, saying, “The defendant was deprived of his right to a preliminary hearing in the district court by the district attorney’s actions in presenting the case directly to the Grand Jury.”

Regardless, the court did not believe these items necessary for Butch’s defense, and on March 11, 1975, presiding Judge John Jones denied the request. With little choice remaining, Siegfried later filed a notice of defense of mental disease or defect for his client. Since the defense had been denied an equal opportunity to have the same reports, records, and photos that the prosecution had in its possession, there was only one choice left: an insanity plea.

Butch did not want his sanity questioned, and he threatened to strangle Siegfried. With little recourse, and after spending more than $40,000 on attorneys, Michael Brigante Sr. told his grandson, “Sweetheart, your dime is played out.” This meant that Butch would have to use a court‑appointed attorney.

On July 7, 1975, William Weber, from the firm of Fredrick Mars and Bernard Burton in Patchogue, New York, was assigned by the clerk of the Suffolk County Court to represent Butch in his trial.

On July 29, 1975, Judge Ernest Signorelli, who was at that time presiding over the DeFeo trial, had a conference between Butch, prosecuting attorney Gerard Sullivan, and William Weber. The major concern was that there were no objections to Weber’s playing an active role in Judge Signorelli’s campaign to be elected to the surrogate court. After everyone agreed Weber’s role in Judge Signorelli’s campaign did not pose a problem, the matter of an insanity defense came up.

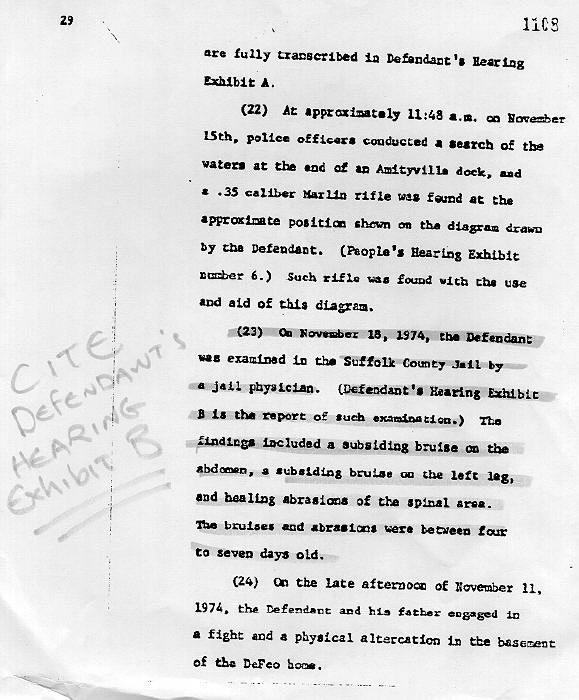

Weber was hoping Judge Signorelli would grant the defense motion to obtain copies of all the police reports and crime‑scene photographs the prosecution had. On August 1, 1975, Judge Signorelli issued a ruling on Weber’s supplemental omnibus motion, granting the defense copies of the reports and photographs in the prosecution’s possession. Since Weber did not receive the documents until the end of August, he had little time to use them in preparation for the trial set to begin September 15.

On September 15, 1975, the defense was also struck a devastating blow when Judge Signorelli announced in a hearing, “I deem it advisable to disqualify myself from the case, and I am going to ask the administrative judge to reassign the case.”

In his book, entitled High Hopes, Sullivan openly admitted that he had an active role behind Judge Signorelli’s dismissing himself. Sullivan added, “…I had not finished maneuvering. I was about to engage in a time‑honored strategy that defense lawyers and prosecutors have honed into an art form. Some called it ‘judge shopping.'”

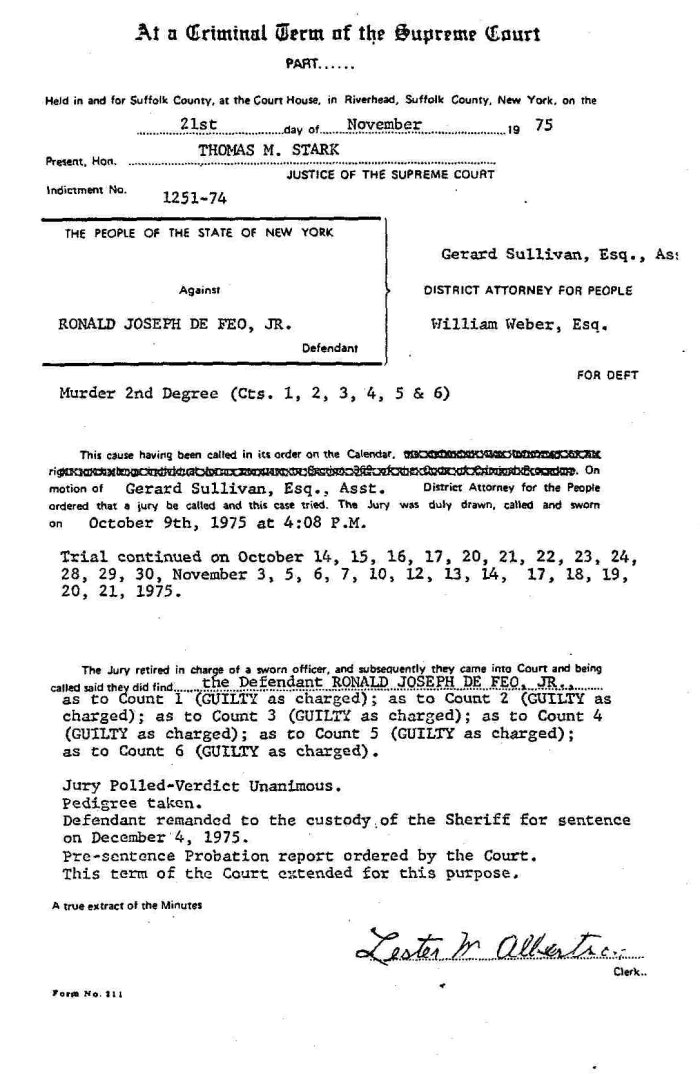

Sullivan helped pressure Judge Signorelli from the case in order to get the judge he wanted. His wish came true because the DeFeo case was rescheduled to begin on Monday, September 22, 1975, at 9:30 a.m., with Justice Thomas Stark—Sullivan’s choice—presiding over it. For his book, Talking with Serial Killers, British Criminologist Christopher Berry-Dee interviewed Justice Stark. Confronting Justice Stark on Sullivan handpicking him, Justice Stark, with a waive of a hand dismissed this, and said, “In hindsight, this was quite wrong, but things were different back then.”

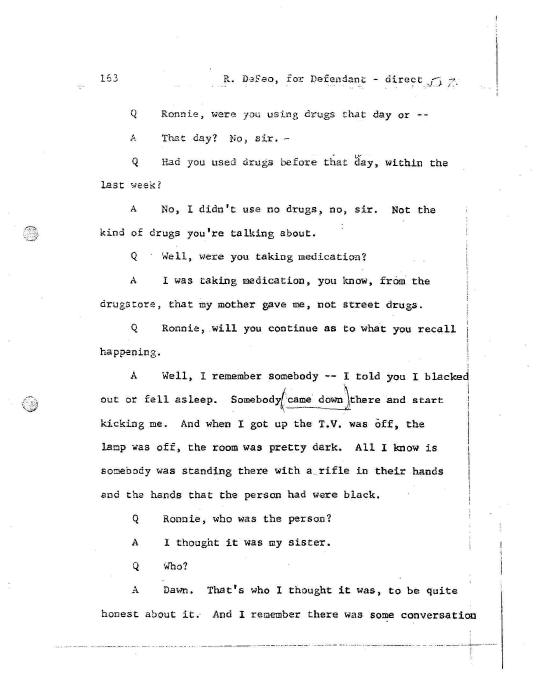

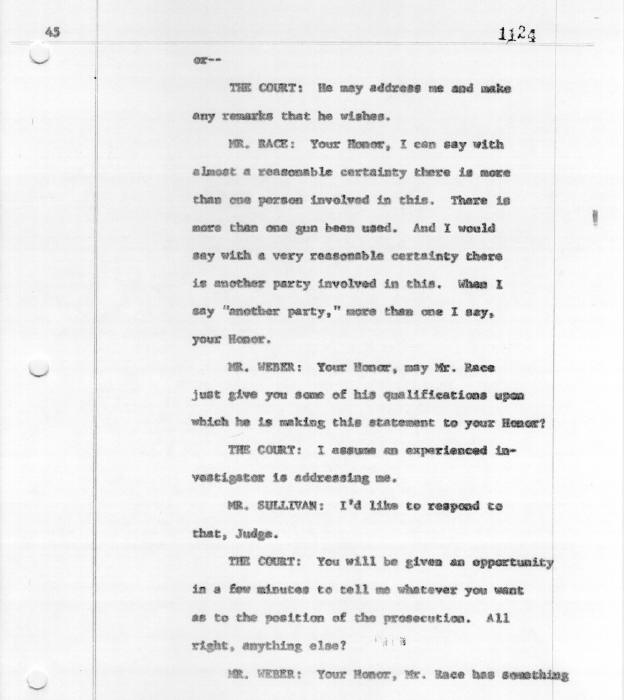

At the outset, in an attempt to nail Weber down on his defense during a private post-hearing conference, Justice Stark asked, “At this time, Mr. Weber, are you prepared to continue our discussion as to the matter of the defendant’s intentions of raising the defense of mental disease or defect?”

Weber replied, “Your honor, I am not able to answer you on that point, at this time.”

Still needing a definitive answer, Justice Stark continued pressing Weber on the issue. Whereas Weber replied, “Your honor, at this point, the only thing I could ask the court to consider is my application for an adjournment of the trial.”

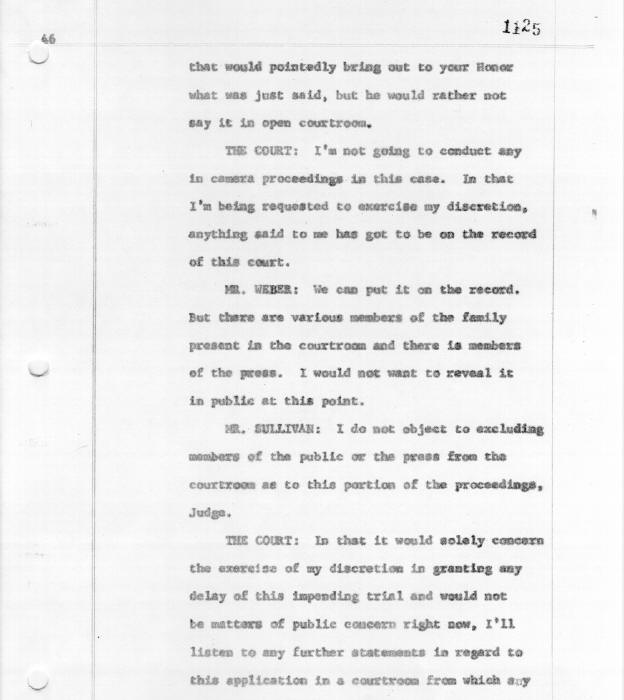

Weber went on to explain to Justice Stark his need for the 60‑day adjournment. Because he had been retained as an attorney only since July, Weber needed more time to prepare his case. Although Judge Signorelli had granted Weber’s omnibus motion on August 1, Weber had not received any paperwork from the district attorney until August 27.

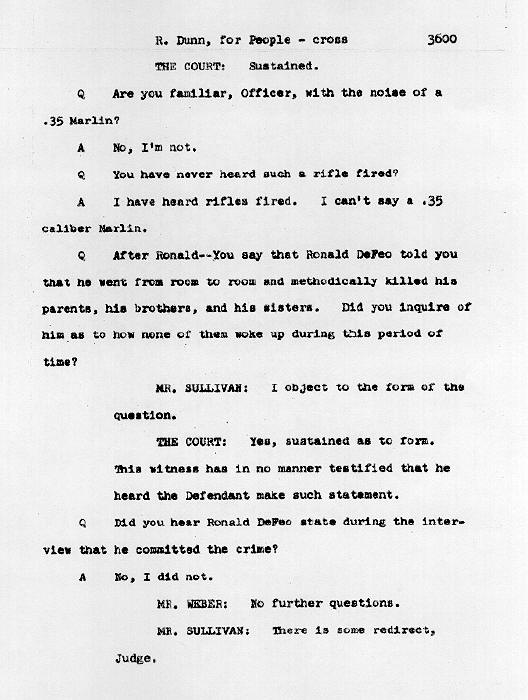

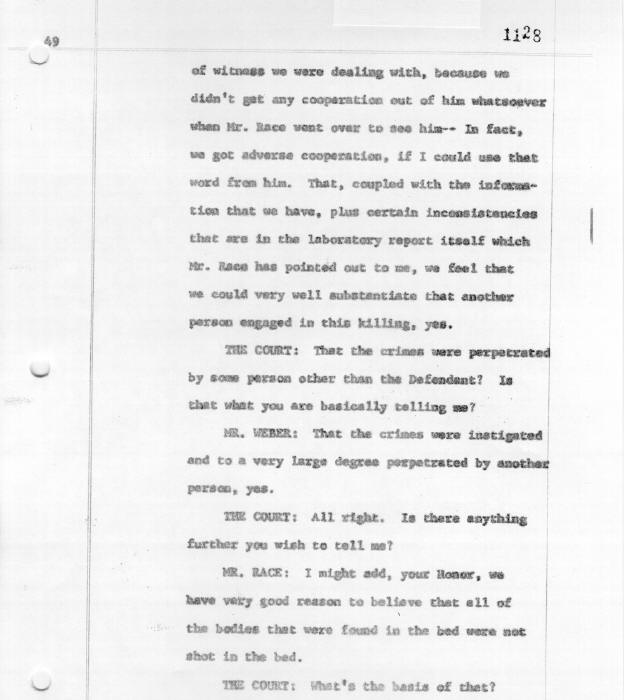

During the post-hearing conference, Weber explained Race’s findings–multiple killers, weapons, and accomplices not being prosecuted. With such an overwhelming amount of evidence, Weber felt an adjournment was appropriate. Besides, Weber argued that the presence of an accomplice, who they named at the post-hearing conference to show that this “witness” was not cooperating, might assist Butch in an emotional strain defense rather than a mental defect one. If an emotional strain defense was used, and successful, then the charge against Butch would be reduced from second‑degree murder to first‑degree manslaughter.

Although William Weber fought valiantly for his client, in the end Justice Stark denied Weber’s request and ordered the jury selection to commence on Monday, October 6, 1975.

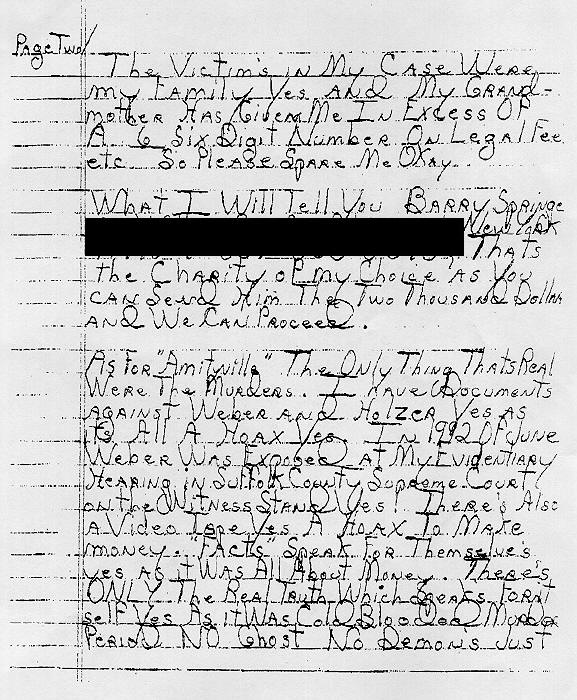

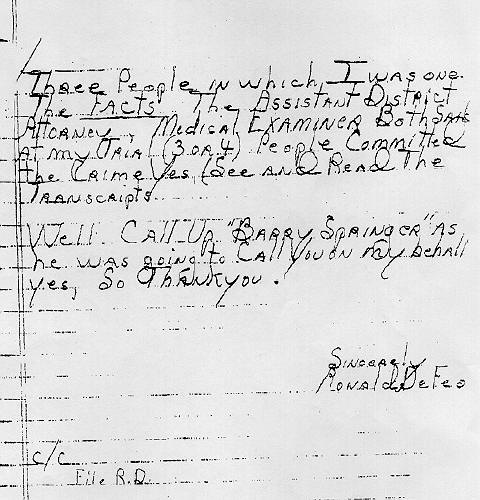

It was clear that Butch DeFeo was not being afforded the fullest protections of the American judicial system, so alternative methods were needed, including persuading Butch to plead insanity by pretending, among other things, to hear voices in the Amityville house. It was the early beginnings of the Amityville haunted house hoax. However, Butch was no actor and his testimony actually backfired when he admitted not hearing any of the so-called voices the night of the murders.

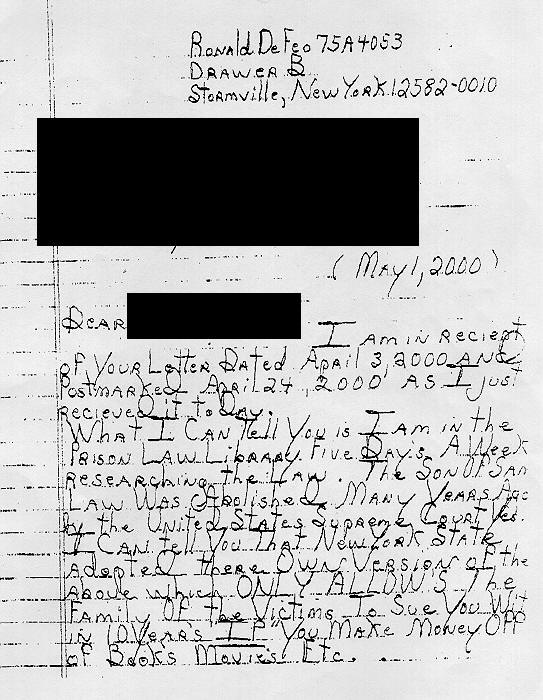

In an affidavit, Barry Springer stated that William Weber had told him that people approached him to write a book even before Butch’s trial had started. Geraldine DeFeo further explained, “Because Butch felt insulted that his insanity could be questioned, Weber had to convince him by alternative means. He promised Butch that he’d get out in two to three years, and that he’d be rich from the book’s success.”

In a notarized affidavit, Geraldine DeFeo admitted to being party to the initial planning of a book before backing out due to ethical concerns.

THE AMITYVILLE MURDERSSocial Media